How the Trump administration endangers hundreds of sacred sites

Each time a federal agency wishes to develop a project in Wyoming – an oil and gas lease, a pipeline, a dam, a transmission line, a solar network – it must first go through Crystal C'Matting. The appearance is northern Arapaho and the head of tribal historical preservation, or THPO, for the northern tribe of Arapaho, so if a new wind farm is proposed, for example, it determines whether tribal areas will be affected by the project.

“It's a difficult job, but I have the impression that it is a really important job,” said it. “I feel a feeling of gratitude that I am able to do this and that I am able to try, in my best capacity, to preserve and protect what we have.”

The scope of C'Ebearing extends beyond his house on the Wind River reserve, to all the land ceded by the treaty, the roads that tribal members took during the withdrawal process, interoncement sites and religious places. This means that it reviews projects in 16 states in addition to Wyoming, Wisconsin in Montana, New Mexico at Arkansas, and from all points between traditional countries in northern Arapaho and other Aboriginal nations, acquired by the United States when it has developed with force to the west. Due to this range, hundreds of federal proposals and reports flood its reception box each week, as is the case with 227 others work for their respective nations. Many have ride historic homelands and stories.

Agents of tribal historical preservation, such as employment, are often a first line of defense against destructive federal projects and rely on a range of skills of traditional ecological knowledge to cultural and historical knowledge of places and landscapes. Now their work is threatened.

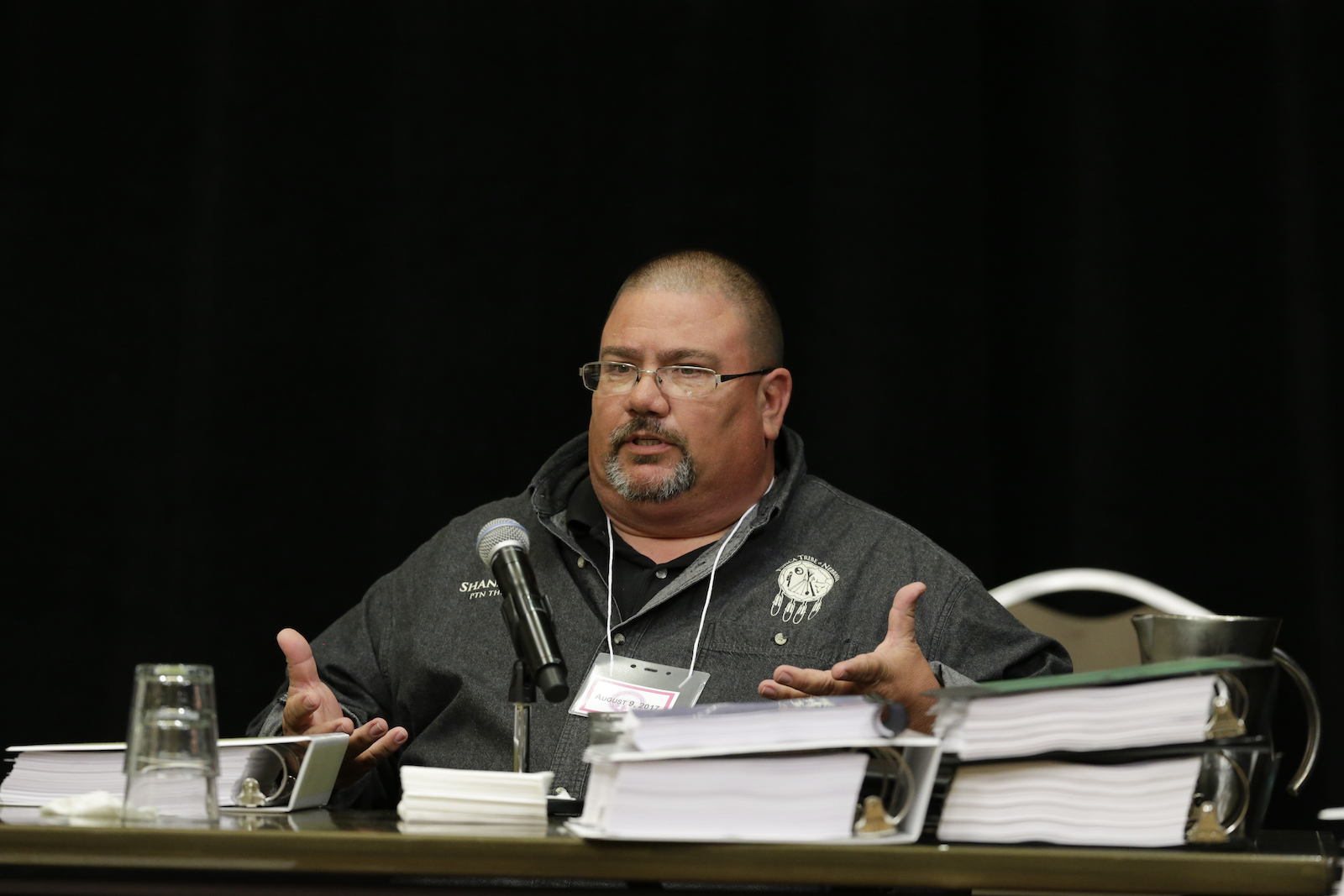

Scott ring / AP photo

In January, President Donald Trump declared a national energy emergency To accelerate the development of fossil fuels, mines, pipelines and other energy -related projects, Cut off time Federal agencies are necessary to inform the indigenous nations before starting a project. Now like Trump Budget offered for 2026 Go through the congress, the fund supporting The national THPO program is compensating For a budgetary drop of 94%. In addition to that, the Trump administration has not yet distributed funds promised for 2025.

Traditionally, THPOs like C’Dering have 30 days to review a project: 30 days to examine federal reports, make sites, identify artifacts or a place of burial and collaborate with tribal members, sometimes other tribes. According to this, this window was already tight, but under the energy emergency of Trump, this deadline is now seven days. And over the year, C'Bearing’s budget evaporates. If the administration does not publish the already promised THPO funds, it will be unemployed in September.

“If this is the moment that breaks the system, there will be nothing to catch the THPO,” said Valerie Grussing, executive director of the National Association of Tribal Historical Preservation Agents.

The THPO program was born from Requirements established by the 1966 national historical preservation law – The legislation responsible for the preservation and protection of historical and archaeological resources in the United States. At the time, public concerns about historical places were modified or destroyed by infrastructure funded by the federal government as well as urban renovation projects prompted the federal government to take legislative measures. The law requires that all federal agencies identify all the impacts that their projects could have in the fields important for states and tribes, and inform the public of these impacts. But the indigenous nations play a particularly important role: agencies must consult tribes, whether the project is located or offered Indian reserves recognized by the federal government. This warning holds inside A broader context of the law and the rights of the treatiesAs well as the federal government's trust responsibilities requiring the agencies to put “good efforts” in consultations.

If a THPO performs its analysis and finds that there is no risk that a federal project has an impact on cultural or historical resources, the plan advances. If a THPO finds that there is a risk, the tribe, the Federal Agency and the State determine an official agreement explaining how the impacts will be resolved or attenuated. This part of the process can take years.

Nati Harnik / AP Photo

With a significantly shorter examination period, however, the THP will have to make difficult choices on the hundreds of reports that intervene every week, the existing backwards and the priority of “emergency” projects at the price of others. This means that the tribes will have no voices in the way projects are determined on their homeland, putting at risk of countless cultural and historical sites. Many of these sites are areas of unspeakable wilderness, as with Pe'Sla in Black Hills – a sacred ceremonial site for Sioux, Lakota and other nations – now facing Exploratory drilling for graphite. Many of the most resilient forests in the world, such as Pe'Sla, are protected by indigenous peoples and offer advantages of attenuation of climate change by storing carbon.

“Often, we still have to throw a deeper look and double check and triple some of these areas, then coordinate through the tribes if necessary,” said Raphael Wahwassuck, Thpo for the Prairie Potawatomi Nation group. “It is quite unrealistic to have a good job in this window.”

In April, 186 projects With an emergency designation, it was authorized to start construction. The designation includes controversial projects such as Line 5 in Michigan, inviting Seven Aboriginal nations to move away federal negotiations. Fifteen states have continued the administration alleging that there is no energy emergency and that the declaration illegally bypasses additional journals of federal projectsas the environmental impact or the evaluations of endangered species.

“My concern is that everyone will use the emergency declaration in one way or another on all these projects and we are just going to be bombed with a ton of them,” said C'Bering. “This is just another thing added to which we have to pay attention, between the other hundreds of things we do here.”

But beyond the truncated examination calendar, funding is exhausted. The approved and appropriate funds for the 2025 congress are still occupied by the management and budget office, or OMB, pending additional Trump administration exam. Neither the OMB nor the White House responded to requests for comments for this story. An official of the Ministry of the Interior said that pending financial assistance obligations, including subsidies, are being revised for compliance with Trump's recent decrees.

“If this continues, monitoring measures must be taken – including legal remedies to enforce the law. This is not a suggestion. It is not optional. The law requires that these funds be spent. ”Wrote an email. She is a member of the Committee of the Credit Chamber. “It is wrong to retain the financing of tribal governments – horribly and legally. Many tribes have been waiting for decades for basic investments in schools, housing and infrastructure for decades. And now, even when the funding has been approved by the congress, they are forced to wait again because of what seems to be a delay in political motivation that violates the law. ”

Despite the excessive importance that things play for the indigenous nations, very few tribes can devote additional funds to maintain these roles. The majority is fully based on federal funding, as the program has been designed, said Grussing, and the allowance has never provided an average of a staff member by office of Thpo, by tribe.

The US government has stolen the Black Hills. Now he clearly cuts them.

“It was more difficult for tribes to prioritize historical preservation than usual. It is generally quite difficult, but now we see similar effects for tribal education, health and housing,” said Grssing. The budget proposed by Trump in 2026 reduces $ 911 million from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Bureau of Indian Education. “The expectation of the tribes intensifies and favors historical preservation during this period is not realistic.”

With financing discounts on several tribal operations points, tribes must make choices such as financing their health and safety – or a THPO program. Wahwassuck's concern is that if several tribes lose their THPO and their staff working on consultation requests, conditions will effectively return to a period of pre-consultation, as in the 1960s. In this world, tribal countries would not have the possibility of intervening or protecting cultural land and resources.

“There have been a lot of benefits made on the blood and bones of our ancestors and land from which our tribes had to yield and be removed,” said Wahwassuck. “I hear that this regularly mentions that this administration wants to recognize tribal sovereignty and honor the confidence and responsibility of the treaties. However, these financing actions go directly to these declarations. ”

Correction: This story initially poorly identified the location of line 5. It also gave the bad affiliation to Raphael Wahwassuck.